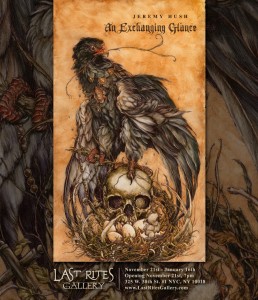

The Jeremy Hush Exhibition at Last Rites Gallery, NYC

21 November 2015 – 16 January 2016

On November 21st, I attended the opening reception for “An Exchanging Glance”, a solo exhibition of new works by Philadelphia illustration artist Jeremy Hush. The title of the show comes from one of the main pieces featured in the exhibition, where a Bateleur eagle sits atop an empty skull that rests in its nest, the piercing stare of the eagle juxtaposed with the vacant human eye sockets. It’s a reversal of dominion (i.e., the thinking of what humans actually assert dominion over) and what that entails. This piece, along with others included in the exhibition, is meant to remind us of the responsibility we have to other inhabitants of this world. In this way, Hush’s work demands that we rethink our roles, definitions, and the ways we understand ourselves as somehow superior to nature. Many works feature humans at moments of extreme vulnerability, or even demise, and with utter emotional vacancy. The plants and animals, on the other hand, are depicted with rich emotional and psychological character. This aesthetic experience comes complete with a massive installation comprised of five wooden rosette arches underlying the works of art.

When I first saw the media for this show, the images reminded me of 17th – 18th century Northern European still-life paintings, the really beautiful but incredibly ominous ones that contain time pieces, skulls, rotting fruit and dead animals, things which serve as symbols for death, life, vanity, earthly pleasures, greed, etc. Hush’s work, like these classic paintings, also holds a cautionary message about our behavior and inclinations towards the world we live in. The golden giant rosette arches, reminiscent of those found in a church surrounding stained glass windows or comprising the alter rails, create a dramatic contrast with both the imagery of the works and the black walls of the gallery. They inspire further contemplation of the things we humans do and why we do them. Religion depicts man as God’s highest creation, the earth with all its plants and animals is ours to use as we like. Often that statement seems to be interpreted as ‘abuse as we like’. Humans have used God not only to commit atrocities against each other, but against Mother Nature as well. Hush’s work forces us to confront the notions we have about our status in this world (i.e., a creature among creatures or an entitled godly beast) and even question the things that supposedly make us superior. At this ‘place of worship’ we do not find imagery of the Good Shepherd holding the docile beast, but rather we discover triumphant aspects of the natural world teaching humans the error of hubris. It’s all very dramatic and oh so stunning to look at.

As a philosopher, the theme was one that deeply interested me because historically great thinkers have attempted to assert and justify humankind’s superiority over nature by way of our rationality: we have big brains and can do logic, therefore we are master over mother nature! (I think, therefore I am the master of the universe.) Yet, we really know and control so little of this world. Hush’s work not only reminds us of the responsibilities we have to creatures great and small, but that this notion of ‘dominion over all’ we have entertained for over a thousand years will never succeed. It’s a fantasy. And given the state of the world at the moment – wars, poverty, racism, climate change, and reality TV – should we really be top beast?

Be sure to check out this exhibition before it’s gone. It’s beautiful, provocative, and insightful.

As for Last Rites Gallery, it’s a wonderful place to take in some great contemporary surrealist art. The gallery strives to display a showcase of thought-provoking art imbued with references to the dreamlike landscapes and ambiguous feelings originated from an intimate, philosophical contemplation of the self. Last Rites invites the observer to reflect inward and abandon himself to a conscious perception of what the innermost recesses of the mind can reveal and produce under the urge to see beyond our apparent limits. The gallery program is mainly focused on figurative paintings and sculptures featured by an unconventional interpretation of the human existence that seems to escape any definition of what is real, unreal or unknown.

About Jeremy Hush:

Born in 1973 in San Diego, CA, Jeremy Hush graduated from the Savannah College of Art in 1997. Inspired by the work of Arthur Rackham and other 19th century illustrators, as well as by the world of punk and heavy metal music, Hush’s imagery is strictly intertwined with the allegories and symbols of nature. To create his works, Jeremy prefers to use found materials such as ballpoint pens from around the world. While drawing and painting in a seemingly traditional way, Hush also experiments with a variety of unconventional mediums and techniques. Jeremy has been included in a number of group and solo exhibitions, and his works can be found in many private collections. He currently lives and works in Philadelphia, PA.

About Last Rights Gallery:

Established in 2008 by Paul Booth, Last Rites has become a premiere gallery for contemporary surrealism and a haven for artists who are not afraid of exploring and dissecting every aspect of the human condition to investigate the invisible, the unintelligible and the inexplicable with a focus on the most recondite twists and turns of reality.

Last Rites Gallery is located at 325 W 38th Street, between 8th and 9th Avenues, New York, NY.

Gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 1pm to 9pm, Sundays 1pm to 6pm.

For more information, please email info@lastritesgallery.com or call: 212.560.0666.